Dado by Isabelle Monod-Fontaine

This text by Isabelle Monod-Fontaine, reproduced here courtesy of the Editions du Centre Pompidou, comes from the catalog Donations Daniel Cordier. Le regard d’un amateur, 2005, pp. 80-93. This piece is reprinted from the catalog to the exhibit “Donations Daniel Cordier,” which took place at the Pompidou Center on November 22, 1989 to January 21 1990.

Click on the images to enlarge them

(large and extra large sizes)

❧

Fullscreen

slideshow

When the tousle-haired young Dado arrived in Paris in 1956, he must surely have looked like a life-size Struwwelpeter (a character he had drawn the previous year), while the adventures of this youthful brave who had just disembarked from another world right in the middle of the Cold War more or less resembled those of that far more famous, unthinking Shock-Headed Peter, who, since 1884, has delighted generations of children.

The superficial opposition between his still rather wild freshness and the chortling world that appeared to follow in his wake, in the form of the procession of gnomes that parade over his drawings, immediately won over a certain audience. The first was Dubuffet who met him at Patris’s, the lithographer for whom Dado worked (sporadically, he says so himself). And very soon after Daniel Cordier’s eagle eye had discerned the violence and “difference” concealed in boxes shipped over from Belgrade – at the time their first meeting Dado showed only him old drawings – and soon the promise of something else; a talent, which on maturing, might well prove truly remarkable.

AM 1983-146 (R). Photo: © Bertrand Prévost – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP.

Right: Untitled, 1956, India ink and red ink wash on paper (on the back of an architectural plan, 50,9 × 36,5 cm), 50,9 × 36,5 cm. AM 1983-144. Photo: © Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP.

As Dado’s observes, Cordier’s curiosity was initially aroused by works that appeared to emanate from another world, a world which surely proceeded, on the one hand, from childhood and from a very personal mythology, and, on the other, from a visual and intellectual culture that had little to do with the French cultural fabric of the 1950s. The Fine Arts School in Belgrade, the avid study of reproductions and art books, rather than any direct contact with painting (Konrad Witz, Schöngauer, in particular), but still more the visions, the war, his childhood in Montenegro, the stories the child heard and his sensitivity, like some extremely powerful lens that captures certain details, monstrously enlarging them, mixing the reality he witnessed with information he gleaned and receptive without distinction to horror and to wonder. “The war also took place without my seeing it, it was at the gates of the city, while me, I saw nothing, I sensed it., That’s why there was this need to kind of scratch., ah! It’s frightening, the first sight of the horror., it’s not complicated. I was going for my usual walk with some pals to see Lake Scutari [: Skadar], some ten kilometers away, and then, from round a bend, yuk!., we were., like bowled over by the stench., but one of improbable violence, the putrefaction, you see. So what was it? Three horses had been dumped there, by the side of the road, in the sun., and behind the three horses there was Lake Scutari [: Skadar], the most beautiful, the most lyrical vista you can imagine!. Because, fifteen kilometers away as the crow flies, you can see the lake. Most of all, there’s all that blue under your nose, the little waves and the fish in it., you can’t see anything, it’s an extraordinary backdrop. It’s surely ingredients like that build into a kid’s mental attitude” (taken from a conversation published in the catalog of the exhibition “Dado”, at the CNAC, Paris, 1970). In fact, this odor of putrefaction and the sublime blue of the lake have lain concealed in Dado’s painting up to the present day. This astonishing and explosive mixture was bound to interest those who rejected the rather chilly, right-thinking abstraction fashionable after 1950…

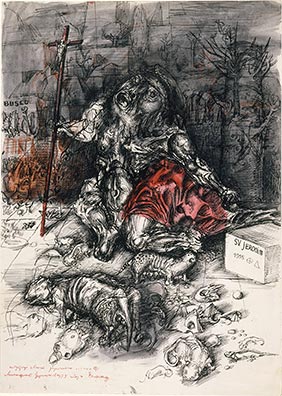

Right: Study for St. Jerome, 1955, India ink and red ink on paper, 45,5 × 33 cm.

AM 1983-148. Photo: © Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP.

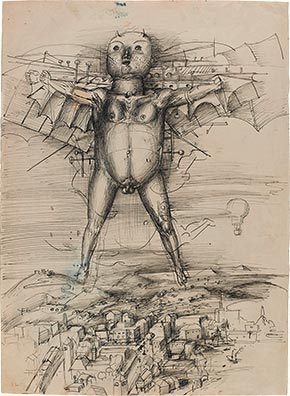

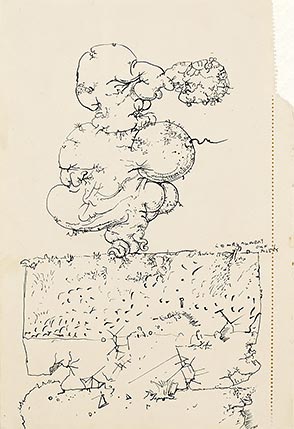

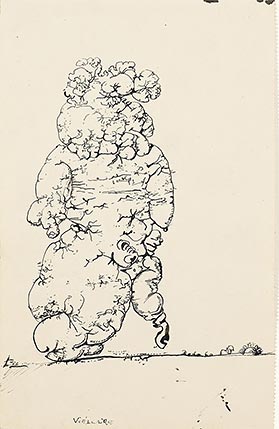

The first series of works brought from Belgrade – dating for the majority from 1955 – introduced a gallery of more or less burlesque characters, old men with children’s heads much too large for their ridiculously tubby bodies. Among the shambles of broken toys, of unshakable rattles, there’s nothing they can rely on: Icarus (like some chubby-cheeked Batman in free-fall), likewise St. Jerome, whose cross appears of no greater help than the kite held by the sinister little cyclist in the Triumph of Death, stand out against an expanse of ruins. Graveyard for toys, rubbish dump, or mass-grave, viewed by a child there’s no great difference between them, and the abundant metaphors become obsessive, persistent. One might wonder moreover about the pseudonym chosen by Miodrag Djuric: two infantile, stammering syllables, pregnant with maternal affection – the sugary coo of the first words babies murmur in every language under the sun. As pulpy as gruel, this iconic “Dado” harks back to the vocabulary of the nursery, cuddly and marginally obscene: it’s hard to imagine it being simply plucked out of the air by someone as sensitive to words and to the music of the voice as Dado.

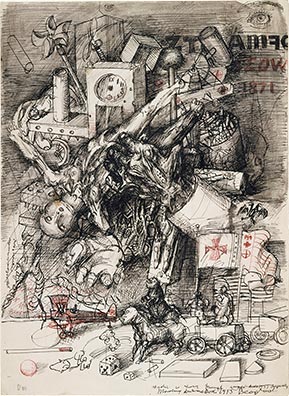

Right: Triumph of Death, 1955, India ink and red ink on paper, 39,5 × 28 cm.

AM 1983-151 (R). Photo: © Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP.

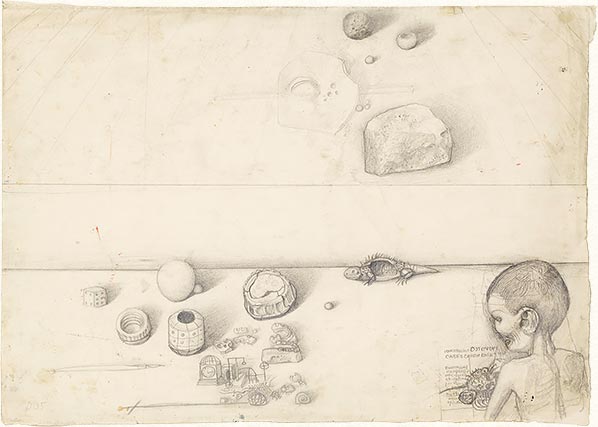

Most of the time in this period one figure dominated all the rest, in a space defined by a relatively low horizon that rendered its gigantic size (and absurdity) even more imposing. But it transpires that this space tended to fill up, being soon chock-a-block with scraps and oddments. The drawing generates itself; countless notes, additions, trills, and variations succeed one another in a universe that, if it dramatically overflows, does not thereby gain in meaning, since the scattered objects cannot be connected to form a coherent whole.

AM 1983-155. Photo: © Bertrand Prévost – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP.

The drawing puzzlingly entitled Trade Union is exemplary in this respect. Stone and cheese, dentures and skeletons, inkpot and skull make do with a deserted field. In its dryness, what it records is undoubtedly still more desperate than the sordid blackness of Love Scene in the Suburbs or than the grimacing avatar of Commedia dell’Arte.

Once in Paris, confronted with a very different environment, with very different preoccupations, the relationships he established with contemporaries – the chance of rubbing shoulders with several generations, with elders such as Dubuffet, Giacometti, and Michaux, as well as his friendship with Réquichot – were all obviously to turn this visionary childhood backdrop on its head. Enriched by certain formal elements, metamorphosed – in every sense of the term – by further research into materials, it never betrayed its fundamental, irreducible and secret inspiration. Starring extras from an irresistibly funny human comedy played out by insane potatoes, one astonishing series of drawings from 1960 demonstrates Dado’s virtuoso gift for making the animate proliferate over the inanimate. These left-field tubers, these unruly rhizomes do not simply sprout from a scurrying pen automatically transcribing the visions of an artist; they also proceed from a capacity to observe and to open one’s eyes in wonder (particularly at what is usually regarded as ugly, unprepossessing, a little monstrous, off-putting: when all said and done, at what we learn to avert our eyes).

AM 1983-159 (R). Photo: © Bertrand Prévost – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP.

Right: Old Man, 1960, India ink on paper, 19,8 × 12,6 cm.

AM 1983-158 (R). Photo: © Bertrand Prévost – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP.

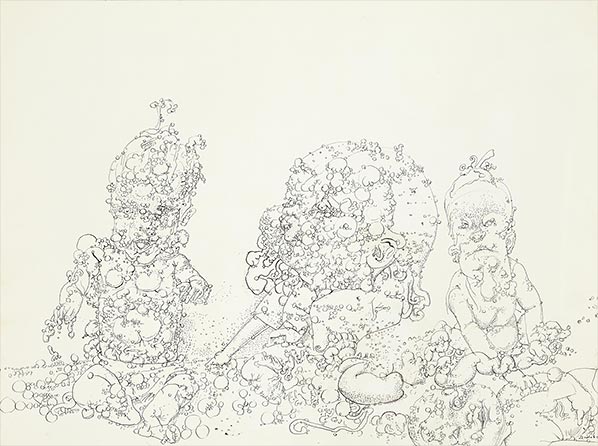

Thus, the “Maunument” to the Dead (1960) is at once Dado’s tribute to Ghirlandaio and to his own grandfather, whose nose, it appears, was adorned with growths similar to those of the famous old man wearing red in the Louvre. Or again the splendid baby Cadum on the posters, designed to melt the heart of every maternal consumer in France, trapped in the foam and bubbles of his favorite soap, transformed by Dado’s mordant eye into a hideous pustulant sprog, a delectably ghastly entity (Untitled, 1960, AM 1983-161). Dado’s line has abandoned the expressionist shadows tinged with foreboding of his beginnings to carve out an (ostensibly) more innocent, translucent space. The treatment that contaminates and desiccates the material of his figures gradually invades this reconfigured space.

AM 1983-161. Photo: © Bertrand Prévost – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP.

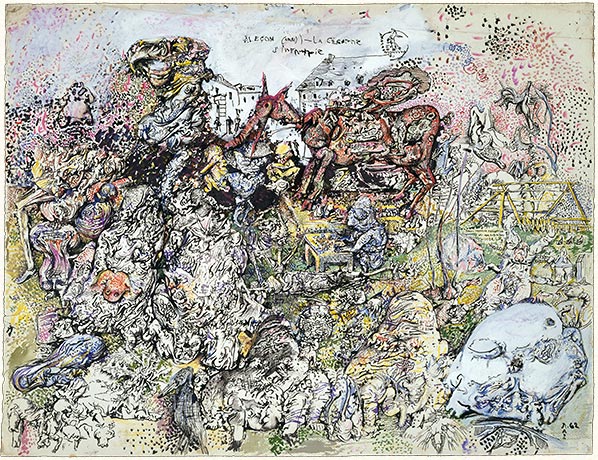

Perhaps reacting to certain works by Dubuffet, Dado’s landscapes and characters appear carved out of one and the same ineffable substance, stone (The Architect [1959], hewn in a kind of limestone and enthroned in a petrified cosmos of its own making) or lichen: “Every ingredient in Dado’s world – the before-term babies, the premature old men, the stones – everything splinters. If there are walls or monuments, they crumble, falling into ruin. Moreover, many of these pink, reddish or sometimes off-white creatures appear to be made out of terracotta or dried clay and on the point of splitting or bursting. They suffer from a fatal thirst in a land deserted by water, devastated by desiccation.” (Georges Limbour, foreword to the catalog for the exhibit “Dado”, Frankfurt, Daniel Cordier gallery, 1960). Dado’s meeting with Réquichot through the good offices of Daniel Cordier proved a turning-point. He often refers to texts by Réquichot and after his suicide painted a tragic and magnificent homage, at once summa and Noah’s Ark, hell and paradise. This is The Large Farm (1962-1963), an exhaustive and generous tribute of a painter to his friend. Surely alluding both to their friendship and their discussions Dado fashions his rosaries of bone and skeins of intestines into ingredients for a new anatomy. From these elements, sometimes worked out separately in detail, there sprung a kind of alphabet. Three drawings dated 1962 from the donation hint at an exercise program, a systematic warming-up, in a terrain that then expanded into the almost unbearable, truly dazzling virtuosity prevalent in other drawings, as in the series “Myxomatosis.” This brings to mind a note by Réquichot (published in spring 1962) about a moment of fascination with which Dado would surely have concurred: “I stop on boulevard Saint-Michel, all of a sudden fascinated by a slice of liver from a cancerous horse displayed in a bottle of alcohol in a storefront. Here is not the place to say how deep, horrid and velvety were the black spots dotted about this piece of meat which, probably browned by the alcohol, resembled the skin of a large slug, since that horror was exceeded by its beauty.” (Bernard Réquichot, “Extrait d’un cahier vert,” L’Arc, 1962, p. 21).

AM 1989-277. Photo: © Béatrice Hatala – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP.

Dado’s trips to the knacker’s yard, his long-held interest in anatomy (in skin whose palpitations and reflections are associated particularly with painting, while bone structure with its constructive edges lies instead for him to the side of drawing) also stems from wanting to look at everything – and especially at the “horrible” side be it visible or hidden necessarily concealed within every form of beauty. To my mind, another passage from the same notes by Réquichot perfectly captures describes the common denominator of the artists who caught Daniel Cordier’s eye – not just Dado and Réquichot, but others, Henri Michaux to start with: “I paint with my nerves, with my teeth, my claws. I’d like to bite, to destroy. I’m tight as a drum. Muscles (are they muscles) whose location I haven’t yet defined stretch to the point of fusing pleasure with pain. Consider the painting surface as a plate receptive to fluctuations in mental tension, a sensitive plate where these tensions can be fixed as they pass over, and which shows, once filled, a graph of a sequence of psychic instants”(Bernard Réquichot, op. cit., p. 22). Surely this “sensitive plate,” where concepts like abstraction or figuration become irrelevant, is the preeminent focus of Dado’s painting.

The source of the images, their contamination and assembly are, however, questions that can be constantly asked anew. The center is though occupied by the house and the mill at Hérouval, the bucket of blood (appearing as an “ex libris”), the children, the animals, the landscape, and the glorious walls of the Vexin. That is what lies closest to him, day after day. But other images, too, more anodyne (such as a series of folksy postcards) or more commonplace (comic strips, for instance) might serve as a trigger, bending to the imagination, to the fancy, to the satirical verve that transforms them. Norman peasants sporting blouses and clogs, countrywomen in tall headdresses are suddenly thrown off kilter, rendered unrecognizable. Sometimes by sheer proliferation, sometimes by the collaging effect (the Surrealist irruption of a whale with legs in the Normandy sky), the starting image is skewed, hijacked, and in consequence seamlessly integrated into the Dado universe. It is he who endows it with his trademark “skin”, a surface attacked from the inside, as if corroded by seething primeval diseases (The Skin of Miodrag is the significant title of a picture of 1969).

AM 1983-163. Photo: © Bertrand Prévost – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP.

Right: Untitled, 1961, India ink, ink wash and watercolor on paper glue-mounted on canvas, 145 × 113 cm. AM 1989-282. Photo: © Béatrice Hatala – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP.

Another recurring theme (especially since 1963) are those “trunk-figures” – truncated would a better word – though this radical treatment has failed to kill them. Popping out from a leg or a hand, they may also result from the futile copulation between a head and some fingers. Vaguely associated with certain inauspicious disasters of the contemporary period (thalidomide babies), these creatures are again spawned by visions from his childhood in Montenegro, still inexhaustible, ready and waiting to bubble to the surface and overrun the broad supremely peaceful scenery of the French Vexin where Dado has taken up residence. Jumble-Sale Cloth (1963-1964), and especially the Untitled drawing (1963) that seems to prefigure it, with the three abortions heaved, like damned souls, into an infernal maelstrom, deprived as they are of any foothold, recall a sickening scene described by Dado in the interview accompanying the catalog to his 1970 show: “It’s once again one of Céline’s ideas, ‘the sodding luck of the human torso.’ I once had the ‘sodding luck’ – or the privilege – of encountering just such a torso. Headless, it had but a hand, an arm with a hand, as well as clothes, because it was a wretch who’d thrown himself under a train in front of the Fine Arts School at Cetinje., we hadn’t seen it. But as we knew the area, I went over with a pal, and there were cops, and then what do we see but a head. [.] The gash was really odd, haphazard. but I did shiver when I saw the hand; the hand’s a frightening detail, the hand.! It’s very curious to see a decapitated body and to tremble at the sight of a hand. A trunk, now that’s absolutely butchery.” (Dado, Entretien, 1970, op. cit.).

AM 1983-171. Photo: © Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP.

But let there be no mistake: the unremitting intent to point out the horror in beauty and the beauty in horror precludes neither laughter, nor humor, nor, above all, tenderness. Daniel Cordier, in the fine text he devoted to Dado (Daniel Cordier présente 8 ans d’agitation, published in the catalog to the exhibition with which his Paris gallery closed down in 1964) rightly insists on the fact: “It seems that human misery has taken refuge in his arms, transforming this frail, youthful-looking man into a colossal prophet of pity and horror.

If one is going to talk about a painter, it behooves one to address his technique, his themes, his inspiration; especially in our age, when these values have replaced others that half a century ago appeared outmoded, but whose absence after their protracted exile now begins to be felt. Thus one expatiates on a disincarnate object floating one knows not where, detached from both maker and beholder. Here and there, voices speak of the ‘new figuration,’ and indeed the return of images from nature into painting does pose a visual problem.

With Dado, we are far from aesthetics; we are in the center of a humanity that bleeds, without verbiage, uncompromising. His images are so upsetting (in the strongest sense – that is, they lodge in the memory), that, long after having gazed on them, we carry them in our hearts, like something remorseful. It would be to the glory of this child-painter to have restored to painting the presence it lacked – a lack about to kill it, without anyone noticing. Dado is the master of a ‘new humanization’. This is no ‘plastic problem’; it calls for heart, as well as a dose of genius.”

Isabelle Monod-Fontaine

© Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2005

Translated from French by D. Radzinowicz